Without Reflection: Varnishing Watercolor Revised & Expanded

Click Here: List of friendly Watercolor Societies for Varnished Work

My favorite studio moments are right before I sign a painting. When it’s successful, there’s nothing like stepping back and seeing the finished watercolor on the easel. I wish everyone could view my work this way — the way I see it in the studio. Not when it’s behind a glass barrier that separates the viewer, and reflects the room’s surroundings like an aspiring mirror.

This is one of several reasons that I began searching for a more novel approach to display my watercolors. A way to varnish or coat them, to break the glass barrier that held back enjoyment of the art, higher sale prices, and appeal to gallery owners.

I had heard of a handful of watercolorists who had varnished their watercolors, but at the time, it was like trying to find the lost basement recordings of your favorite band. There wasn’t much information out there about the techniques, or what the best practice was.

There were a lot of questions about permanence or longevity, and a lot of claims from both artists and manufacturers. But just because a product says “archival” on the label, how do we really know that it is? If someone tells me using wax medium is a great idea, can I trust that? (I’m not so sure that it is.) What do museums and conservators think about what artists are doing, and does it even matter?

As I write this, years later, there is a growing interest in varnishing watercolors, and there is more information available than ever before. Some of it is confusing, some contradictory. I’ve learned a great deal, and I’m happy to share it. But first, the obligatory disclaimer: I’m not a chemist, conservator or expert of any sort, so I have relied heavily on those who are. And the journey has taken me to points near and far.

The paper I use is from Fabriano, Italy, and I’ve been there to see how it’s made. I’ve gone behind the scenes in Seattle to learn how Daniel Smith paints are ground, and talked to their chemist about pigments and testing for lightfastness. I’ve toured the Golden Artist Colors facility in New York, and talked to the fine people there about Aquazol, varnishes, and conservation methods.

All this is to say I’m serious about getting the best information I can, and I’m committed to sharing what I continue to learn. But always do your own homework. I’m not paid by any of the companies I recommend. There are lots of great products out there. Naturally some are better than others. Experiment for yourself and find what you like.

The Substrate

Varnishing requires a rigid surface, so let’s start with the support and progress from there to the final top coat.

I’ve written before about why I like panels, and aluminum composite material (ACM) is a durable, light-weight, archival surface that won’t warp or bend with humidity, temperature change or corrode if properly sealed. I’ve tried other panels, and I know some artists like Gatorform, but it contains chemicals not welcome in preservation settings.

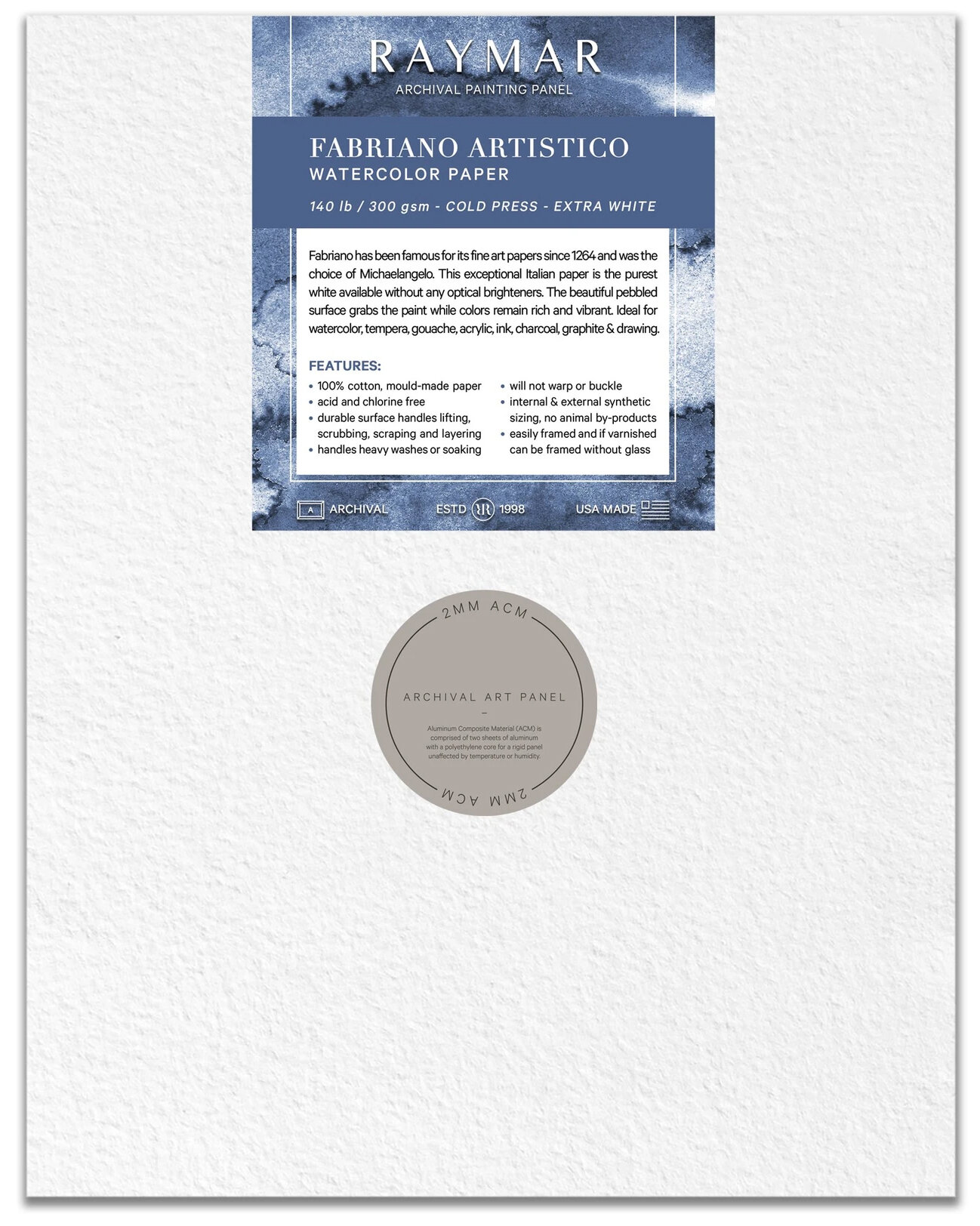

Of course, paper choice is very important for artists, and for reasons I won’t get into here, I prefer Fabriano Artistico. No matter what your preference is, the first step is mounting the paper to the panel, and I use Golden Soft Gel medium as an archival adhesive, applied in three layers.

Step 1: Brush medium to the back of the paper, and also to the panel. Take care and be sure you do not get any on the front of the paper, as this will ruin your painting surface. Allow these applications to dry separately. This creates a uniform acrylic surface on both.

Step 2: Apply a third layer of medium to the panel and fix the paper on top. The reason for this is because acrylic pressed next to acrylic will eventually bond, so even if a spot is missed when applying the third layer, you will still have a uniform seal.

Step 3: Depending on the size of the panel, it may be necessary to use a brayer to roll out any air pockets, rolling from the center out to the edges. Make sure your watercolor paper stays clean by putting a fresh sheet of tracing paper or similar on the surface, then stack your heavy art books on top and let it dry overnight.

Prepared Panels

This process can be time consuming and if you are mounting a finished painting (as I used to do) it is also very stressful. Using a prepared panel with a paper I trust has allowed me more painting time. I’ve been working with Raymar on a product that eliminates all of the work upfront. They offer Fabriano Artistico Cold Press ACM Watercolor panels in standard sizes up to 20 x 24 in. Custom sizes can also be ordered, up to 4 x 8 ft.

For me, the time saved is worth the extra cost. If I mess up a painting on a panel (and I have), it’s easy to adhere a new sheet of paper on top, using the method above, and start the painting over. The panel is not wasted. Raymar also offers raw ACM panels if you prefer to mount your own paper of choice.

After a major screw-up, I mounted a second sheet of paper on the Raymar panel and trimmed it down.

I’ve enjoyed painting on these panels for my realistic style, but there is a learning curve and it takes getting used to. If you want to try a Raymar watercolor panel, you can use coupon code BIRD20 for 20% off (note they are sold in packs of two).

Varnishing

Once you have your completed watercolor painting, you can frame the panel traditionally, or with spacers to keep the surface from touching the glass.

Or you can coat the painting, fundamentally changing the surface and how it looks. There are two points to make in this regard. If you are a purist, it’s important to understand that adding a varnish permanently changes the nature of the painting by adding an acrylic coating. There are also aesthetic changes to color, value, texture, and sheen.

The products used and the order of application in varnishing can be confusing at first, so it’s important to understand why things are done to fully understand what you want to do. It can be a simple one step process, or a more complicated, three step procedure. The decision is based on whether you want the top coat layer to be removable at a later date.

The first step in varnishing permanently locks down the water-soluble paint surface with an archival aerosol spray. There’s no way to brush on a varnish without disturbing the paint layer. (Brushing on a mineral spirit varnish won’t activate the pigment, but it sinks down into the paper, which is not what you want.)

Once the painting is sealed, an isolation coat can be applied. Then any subsequent varnish layers can be stripped down to the isolation coat, and a fresh or different varnish applied.

Why would you want to do this? Because we don’t know where our paintings will end up once they are purchased or how they will be cared for. Over time, dirt, smoke, pollen, even bugs, could build up. Or, perhaps you just decide you’d like to try a different finish than originally applied. Although not necessary, these extra steps would allow for the removal and replacement of the varnish.

I strongly recommend you practice and test throughly before trying this on a finished painting.

Step 1: Seal the painting with gloss varnish

Spray at least 6 coats of Golden Archival Gloss Varnish on your finished painting. Gloss preserves the greatest color clarity in the final result and is recommended for all early layers when varnishing. Satin or matte products can reduce the clarity due to the particulate that diffuses the light, and at early stages, this could leave a cloudy or dusty look. These products are available in aerosol cans, or in larger quantity for HVLP guns (High Volume Low Pressure). Proper ventilation is important! If you don’t have a spray booth, you can go outside, but wear the appropriate respirator.

If you don’t have a spray booth, be sure to use a well-ventilated area or go outside.

Tips:

Spray with the painting vertical or at a slight angle (not flat on the floor)

Rotate the painting 90 degrees each time to ensure the varnish covers everything. This is especially important if you use rough or cold press paper.

If using an aerosol can, shake well for 2 minutes and keep the can warm

Don’t spray from too far back, particles can dry in the air before reaching the surface

Room temperature and humidity can affect the results, be sure to read manufacturer’s guidelines.

Once this is done, you will be able to brush on the next step without disturbing or reactivating the paint layer. It’s important to note that everyone is different, and some may apply with a heavier hand, thus requiring fewer coats. But too much at once will cause drips or runs, so practice your technique.

A wet cotton swab is used test the painting is sealed.

You can use a wet cotton swab to test a corner of the painting and see if the pigment is fully sealed. Roll or brush it gently over the edge of the painting to see if there is any pigment lift. If not, then the painting is sealed and ready to move on. In traditional framing, this test area will be hidden under the frame rabbit, so if paint is lifted, it will be hidden.

Alternatively, you could tape a test strip of paper with watercolor to the side and varnished at the same time. Test this instead of the actual painting.

These coats permanently bind to the paper and technically change the surface of your painting. It’s no longer “pure” watercolor.

At this point you could and stop here (or apply Archival Matte, Satin, or Semi-Gloss for a different finish) and frame your painting as desired. The following steps are only if you want to be able to remove a subsequent varnish layer.

Step 2: Isolation coat

According to Golden Artists Colors, the definition of an isolation coat is: a clear, non-removable coating that serves to physically separate the paint surface from the removable varnish.

This is your backstop, a clear acrylic film that acts as a permanent barrier. Anything applied after this can be removed. An isolation coat can be applied with a brush or sprayed with an airbrush or spray gun. More technical info can be found on it here.

If you are pinching pennies, you can use the Soft Gel Gloss diluted 2 parts Gel to 1 part water in lieu of the Isolation Coat product.

This coat will dry clear, although depending on how thick the application, it may appear milky at first. The isolation coat should cure for 1 day before Polymer varnishing, 2-3 days for MSA since there is a switch from water-based to mineral spirit-based product. It is important not to trap water under the varnish.

Step 3: Varnish top coat(s).

This step is where you have lots of options, not only in the aesthetic finish (gloss, matte, satin) but also application via brush or spray, and mineral spirit acrylic (MSA) or water soluble polymer.

GOLDEN MSA Varnish w/UVLS: Mineral Spirit Acrylic (MSA) with UltraViolet Light filters and Stabilizers (UVLS) can be the same product used in step 1 to seal the painting. It comes in an aerosol can, or you can mix your own and use a HVLP gun. The formula for this dilution is 3:1 varnish to solvent for brush, 2:1 for spray. If using a brush application, MSA levels out more evenly because it is a mineral spirit based resign.

GOLDEN Polymer Varnish with UVLS: This is a water-based acrylic polymer varnish also with UVLS to provide protection from ultraviolet radiation. The formula for this dilution is 4 parts varnish to 1 part water for brush, 2 to 1 for spray.

At Golden, they use a QUV accelerated weathering tester that reproduces the UV damage caused by sunlight that occurs over years. The MSA Varnish was tested for three different durations: 400 hours (33 years of gallery lighting), 800 hours (66 years), and 1200 hours (99 years) and the protection was shown to be almost identical to Tru Vue Optium Museum Acrylic protection.

Both of these products are available in gloss, satin or matte finishes, and both are removable for conservation purposes.

The choice of application is a personal one. The best way to achieve an even coating of varnish is to spray apply. But that is not always practical and I prefer to use a brush. I use a da Vinci soft synthetic hair mottler, (flat wash, short handle, size 50) and apply with the painting flat so there is no running. A little goes a long way, so don’t submerge the brush too deeply. Keeping the varnish from under the metal ferrule will make it easier to clean and extend the life of your brush.

Framing

Now for the easy part! No longer is framing a tedious chore of cutting and assembling mat boards, backing sheet, plexi and dust cover. I pop the panel into a frame and hang it up.

If you want to go for extra credit, conservators will love you if you adhere a sticker to the back of your painting that details the layers and products you have used.

A Note on Exhibition

Conservators will love you if you document your process on the back of your painting.

More and more watercolor societies are allowing varnished watercolors. Obviously, any group that allows mixed media would accept it, but be sure to read the framing requirements in the prospectus, plexi may still be required. For those interested in exhibiting in society shows, I keep a growing list of organizations that accept coated paintings, which include :

National Watercolor Society

American Watercolor Society (maybe varnished, but plexi required if included in the travel exhibit)

Watercolor USA

If you know of other major shows that allow varnished paintings please let me know or leave a note in the comments.

Coating watercolor remains a new frontier for the medium, and while it is not for everyone, the door is open wide for those who wish to safely display and sell their work without glass, using archival techniques.

I am thankful to Cathy Jennings and everyone at Golden for their time and expertise in testing these products. I am also thankful to the handful of artists who have shared information with each other in the search for quality results.